blog

SEPTA cuts create an unsolvable math problem for Center City

SEPTA’s newly enacted service cuts, which eliminate nearly three dozen routes and reduce service significantly on all others, will have widespread impacts across our entire region. Many of these have already been well-articulated by civic leaders, major employers, politicians, urban planners, traffic engineers, and environmentalists: Congestion will worsen, commutes will lengthen, and air quality will diminish. Those with means and choices will get back in their cars to commute, and those without will find themselves facing impossible decisions around buying cars they can’t afford, quitting jobs they can no longer reach in any reasonable way, or waking up before dawn to make it to class on time.

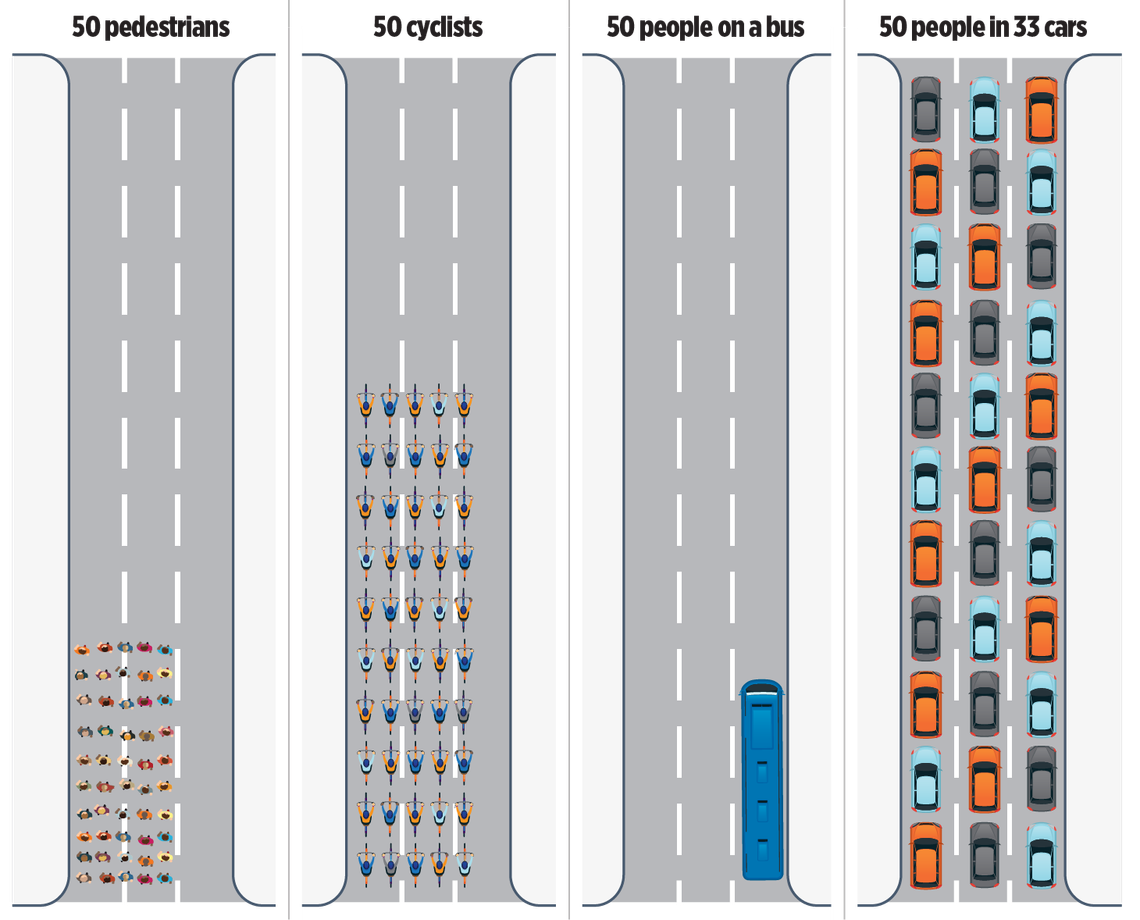

For Center City Philadelphia, there is an added problem that can be best summarized as one of geometry: we simply cannot fit enough cars into the street grid or the parking supply to thrive without public transit. There are many popular versions of this math problem readily searchable on the internet. The Philadelphia Inquirer published its own visualization of this idea in 2019:

This diagram shows how modes of transportation use road space in very different ways. Public transit minimizes space used per traveler, while driving maximizes it. Source: The Philadelphia Inquirer (2019)

While straightforward in the abstract — cars take up more space per person than any other mode of transportation — SEPTA’s funding crisis is forcing us to think immediately and specifically about what this might look like as it plays out across Center City’s centuries-old street grid. To that end, Center City District (CCD) used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) to do some math. Our goal was to apply the Inquirer’s diagram to the actual geometry of our roads.

CCD looked at every arterial street between Pine Street, Vine Street, and the two rivers, removing lanes devoted to parking, loading, bikes and buses to understand how much space for cars exists in travel lanes. The short answer: about 21,000 cars. This many cars can physically fit within the approximately 3.8 million square feet of travel lane space inside this Pine-to-Vine box, assuming bumper-to-bumper conditions and no cars blocking intersections. Adjust any of these assumptions and the total can go up or down by several thousand cars (assuming the average car is just one foot longer, for example, brings the count down to around 19,000 vehicles).

We are putting aside a lot of nuance here on purpose. We aren’t specifically accounting for Amazon vans and other delivery trucks, despite 2023 data from Replica suggesting that there are more than 6,100 freight trips a day into this geography. And we aren’t distinguishing between personal vehicles and rideshare, even though trips in Ubers and Lyfts have doubled since 2019. The point here is that about 21,000 typical cars can theoretically fit in the street grid at any given moment.

CCD's analysis measured total space for moving cars on the streets that make up the Core Center City street grid: Pine Street to Vine Street. Source: Center City District.

This is not the same thing as capacity. For cars to actually move, there must be space in front of them to travel, space next to them to change lanes to avoid a stopped vehicle, space around the corner to make a turn onto an intersecting street. So, the actual capacity of these roadways is nowhere near 21,000 cars at a time if we want people to actually reach their destinations.

The problem with this is that 350,000 to 400,000 people come to Center City on any given day. Despite the fact that some share of office workers have not returned to the office, there are still as many as 130,000 inbound commuters to Center City on a weekday in 2025, and as many as a quarter million or more visitors arriving for conventions, dining, shopping, entertainment, medical appointments, etc. Focusing just on those inbound commuters, our roads can only accommodate about 1/6 of them at any given time, and again that is assuming at a level of total gridlock.

But that assumption is unrealistic. Let’s assume that half of all visitors walk, bike, or take transit (even in its less frequent and convenient form). And then let’s assume that of the 175,000 remaining visitors, carpooling catches on. Even if we get the number of cars down to 100,000, we have space to park fewer than half of them.

There is no way to create more capacity on Center City roadways without creating additional negative externalities. Could parking lanes be eliminated to create more space for driving? Sure. Just ask any civic association how conversations around removal of parking tend to go (more than 60,000 residents occupy the Pine-to-Vine area). Could bike lanes be eliminated to create more space for driving? Sure. But then some share of the 18,500 bike trips made into Center City everyday would become Uber rides or personal car trips, adding more motor vehicles to the roads. Could loading zones be eliminated? Sure, but the 1,792 retail, restaurant, and service businesses we have in Center City storefronts would be unable to restock inventory or maintain operations. Could sidewalks be narrowed to create more traffic lanes? On a couple of select streets, sure, but keep in mind there are more trips made on foot in Center City every day than in cars. That, and walkability is frequently cited as among our greatest natural amenities and economic advantages as a place to work, visit, and live.

Take any of these scenarios to their extreme and it is clear that they become untenable. In the near-term, however, it’s important to return to that relatively low number of vehicles it takes to achieve complete gridlock — 21,000 — and consider the more subtle quality-of-life implications. A car-choked Center City is:

-

Louder: Motors run, brakes screech, and cars honk (particularly on roads where people aren’t going anywhere fast).

-

Smoggier: Cars generate the most exhaust when standing still.

-

Hotter: The urban heat island effect is exacerbated by the heat generated from thousands of running engines.

-

More dangerous: The more traffic an area has, the greater the likelihood of traffic crashes and serious industry of other drivers, pedestrians, and cyclists.

-

More stressful: Gridlock means frustrated drivers, anxious pedestrians, canceled appointments, delayed meetings, ruined dinner dates, missed opening acts.

-

Less pleasant: Nothing degrades the experience of enjoying an urban environment faster and more jarringly than a traffic standstill.

-

Less marketable: With this as the baseline condition, how do we encourage new businesses to locate here, and what incentive would existing ones have to grow?

Adding cars, congestion, noise, traffic, and frustration into the Center City experience is a zero-sum exercise with rapidly diminishing returns. How often would an office worker on a hybrid schedule opt to venture into the office? How eager would a first-time tourist from New Jersey or New York City or Kansas or Europe be to return or tell their friends and family to include Philadelphia in their next trip? How many residents would enjoy stepping out of their front doors into the center of it all if “the center of it all” is a cacophony of car horns, disgruntled drivers, and furious jaywalkers?

Center City Philadelphia isn’t just walkable because it has sidewalks and stores. It is walkable because it can be efficient, pleasant and even downright fun to experience as a pedestrian. There’s a reason why foot traffic and retailer revenue both jumped considerably during Open Streets: West Walnut last year. It’s the same reason why CCD is bringing back the program for six installments instead of four this fall. Walkability is part of Center City’s secret sauce. It’s good for businesses. It’s what differentiates us from so many other U.S. downtowns, aligns us with some of the most beloved urban metropolises around the world, and enables any individual in the downtown to work, shop, eat, socialize, and stroll with convenience and ease.

The Inquirer published that diagram illustrating roadway usage in 2019 when Center City was grappling with congestion as a byproduct of its remarkable success and growth. Managing congestion was a shared concern specifically because Center City’s momentum stood to be jeopardized if we couldn’t figure out how to move people, goods, and services more safely and efficiently. Fast forward to 2025, and the congestion we’re staring down in light of SEPTA’s forced reductions in service is potentially the beginning of a more sinister cycle. The harder Center City is to reach, and the more unpleasant it is to navigate once you’ve arrived, the less inevitable growth of any kind becomes.

There are nearly a quarter of a million jobs just within the core area of Pine-to-Vine, another 50,000 in Greater Center City, and 85,000 across the Schuylkill in University City, which is comparably dense (and transit dependent). SEPTA’s avoidable cuts put the two largest employment hubs of the entire region at risk. In so doing, they challenge the economic competitiveness of Philadelphia writ large while also degrading its quality of life and its appeal as a place to spend voluntary time and money.

This geometry exercise is about showing what and who can fit in Center City. The quantitative part of that is critical to the property owners within CCD’s boundaries: enabling access and movement to and through Center City by a well-balanced mix of modes is what maximizes real estate value. The more people who can be here, and who want to be here, the more it makes sense for an office tenant or retail storefront to plant roots here.

The qualitative implications of this math problem are of concern to anyone with a connection to Center City. A certain amount of congestion is a given for bustling downtowns here and around the world. But past a certain point, the inherent virtues of a place are not enough to overcome the downsides of reaching it, and the aggravation of spending time in it.

Sustainable funding for SEPTA protects Center City’s character, enabling the strolling, shopping, dining and discovering that has made it a destination for decades. Letting SEPTA fail will clog Center City’s arteries, and in so doing, the downtown of Pennsylvania’s largest city will cease to be the region’s heart of commerce, culture, and connection.